Unit-test evolution

29 Oct 2010TDD is not absolute goodness. Tests can be different.

Let’s consider how bad can be unit-test and how can it evolve.

Typical test

This is an example of unit-test evolution which I presented on recent devclub.eu workshop. Let’s consider 3 revisions of the same unit-test class. This is the first revision of this class:

public class ReferenceNumberTest {

@Test

public void testValidate() {

assertFalse( ReferenceNumber.validate("1234567890123") );

assertFalse( ReferenceNumber.validate("1234567") );

assertTrue( ReferenceNumber.validate("12345678") );

}

}

We call it a typical unit-test. It’s not ideal: it fixes behaviour, but does not explain it. Why is “12345678” valid? Why “1234567” is not? One monolithic test verifies multiple requirements. If one check fails - the whole test fails.

Good test

At some moment, some developer decides to apply some TDD best practices and split this test-method into 3 with some meaningful names. This is what he got:

public class ReferenceNumberTest {

@Test

public void testTooLong() {

String len13 = "1234567891111";

assertEquals(len13.length(), 13);

assertEquals(ReferenceNumber.validate(len13), false);

}

@Test

public void testTooShort() {

String len7 = "1234567";

assertEquals(len7.length(), 7);

assertEquals(ReferenceNumber.validate(len7), false);

}

@Test

public void testOk() {

String len8 = "12345678";

assertEquals(len8.length(), 8);

assertEquals(ReferenceNumber.validate(len8), true);

String len12 = "123456789111";

assertEquals(len12.length(), 12);

assertEquals(ReferenceNumber.validate(len12), true);

}

}

We call it good unit-test.

Executable specification

After some time, some developer decides that even this good unit-test is not human-readable and does not provide enough information about how class ReferenceNumber should work. He continued splitting and renaming. This is what he got at the end:

public class ReferenceNumberTest {

@Test

public void nullIsNotValidReferenceNumber() {

assertFalse(ReferenceNumber.validate(null));

}

@Test

public void referenceNumberShouldBeShorterThan13() {

assertFalse(ReferenceNumber.validate("1234567890123"));

}

@Test

public void referenceNumberShouldBeLongerThan7() {

assertFalse(ReferenceNumber.validate("1234567"));

}

@Test

public void referenceNumberShouldContainOnlyNumbers() {

assertFalse(ReferenceNumber.validate("1234567ab"));

assertFalse(ReferenceNumber.validate("abcdefghi"));

assertFalse(ReferenceNumber.validate("---------"));

assertFalse(ReferenceNumber.validate(" "));

}

@Test

public void validReferenceNumberExamples() {

assertTrue(ReferenceNumber.validate("12345678"));

assertTrue(ReferenceNumber.validate("123456789"));

assertTrue(ReferenceNumber.validate("1234567890"));

assertTrue(ReferenceNumber.validate("12345678901"));

assertTrue(ReferenceNumber.validate("123456789012"));

}

}

We call it BDD style specification. It explains requirements. It explains how code should behave and why. It explains customer’s expectations.

And finally, the most interesting part. I had to show this example on devclub.eu session. But.. at some moment I discovered that I haven’t copied the original source code of the class ReferenceNumber being tested.

Panic!

One day left!

I had to urgently re-create it from scratch! Now look at these 3 test-classes, and imagine, which of them helped me to create class ReferenceNumber.

And finally, BDD

You could observe that the third test is different because it describes behaviour of class. It’s accomplished by using words «should» and «contain»: «my class should behave like that», «my method should do this».

So, BDD idea is to use words “spec” and “should” instead of «test» and «assert». Yes, the difference is only a few words, but it makes tests (sorry, specifications) more readable, and writing tests before code more natural for human brains.

You can make sure in it if you look at the same example translated from JUnit to Easyb:

description "ReferenceNumber"

it "should not be null", {

ReferenceNumber.validate(null).shouldBe false

}

it "should be shorter than 13", {

ReferenceNumber.validate("1234567890123").shouldBe false

}

it "should be longer than 7", {

ReferenceNumber.validate("1234567").shouldBe false

}

it "should contain only numbers", {

ReferenceNumber.validate("1234567ab").shouldBe false

ReferenceNumber.validate("abcdefghi").shouldBe false

ReferenceNumber.validate("---------").shouldBe false

ReferenceNumber.validate(" ").shouldBe false

}

it "valid reference number examples", {

ReferenceNumber.validate("12345678").shouldBe true

ReferenceNumber.validate("123456789").shouldBe true

ReferenceNumber.validate("1234567890").shouldBe true

ReferenceNumber.validate("12345678901").shouldBe true

ReferenceNumber.validate("123456789012").shouldBe true

}

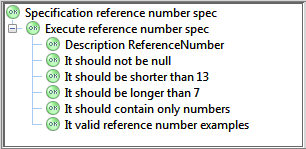

Test report can server as a documentation:

In addition to it and should, BDD also suggests using other keywords, such as given, when and then, also before and after, and ensure, narrative and «should behave as».

BDD suits not only for unit-tests, but also for functional/integrations tests. You can see that tests can be different.

I must remain that there is also a plenty of BDD frameworks for different languages: Java (JDave, JBehave), Ruby (RSpec, RBehave, Cucumber), Groovy (Easyb), Scala (Scala-test), PHP (Behat), CPP (CppSpec), .Net (SpecFlow, Shouldly), Python (Lettuce, Cucumber).

But if you still need to use JUnit — it’s also ok, just remember the third example. And try using Harmcrest with JUnit.

Do you feel BDDevolution?

Complexity is the path to the dark side

Complexity is the path to the dark side